Guest post by Judy Cohen

If you love post-war Italian films as I do, I hope you’ll appreciate the following list of cinematic terms in Italian and English. Each one is explained in English. I include images as examples, describing their function in the context of the film. The goal here is not for you to memorize the terms necessarily, but rather to understand how these techniques are used in post-war Italian cinema (and beyond). This can deepen your appreciation of these rewarding films.

I’ve included links to the cineracconti (photo-stories) on our blog Liconoscevobene.net, and I hope that the glimpses of the films will inspire you to read more. Our cineracconti are published in serial format, episode by episode, and cover the action of the entire film, including dialogue, scene description, and cultural notes, with Italian and English side by side. You can subscribe at: https://www.liconoscevobene.net/subscribe

Buona lettura!

1. The Nuts and Bolts: Shots and Cuts

(Vittorio De Sica, 1948)

(Roberto Rossellini, 1945)

(Federico Fellini, 1957)

(Vittorio De Sica, 1951)

La macchina da presa – the camera

La ripresa – filming

Un’inquadratura – a shot

Filming refers to the uninterrupted operation of the camera. It may be characterized by the distance from the subject, by the angle of view, by the type of camera movement, and so on.

A shot is one still frame. (Technically, a shot is an uninterrupted recording from the time the camera begins rolling until it stops. Our definition expresses the common usage: what the viewer sees as a photograph.)

Our first images are some of the most iconic shots in post-war Italian cinema.

Gino smiles at his son Bruno as he sets out with his new bicycle for a job.

Calling out, “Francesco!” Pina runs after the German truck that is carrying her fiance and other men to labor camps.

Cabiria is put under a hypnotic spell in a theater.

Warming rays of sunlight cast their magic in the shantytown.

These unforgettable shots combine storytelling and visual beauty. Anyone who sees them feels their impact, whether on the first viewing or the twenty-first.

Un primo piano* – a close-up

A close-up generally shows the head and shoulders of a subject, often with space for other aspects of the scene. Close-ups may be used to reveal details of expression or emotion and to bring the spectator closer to the subject.

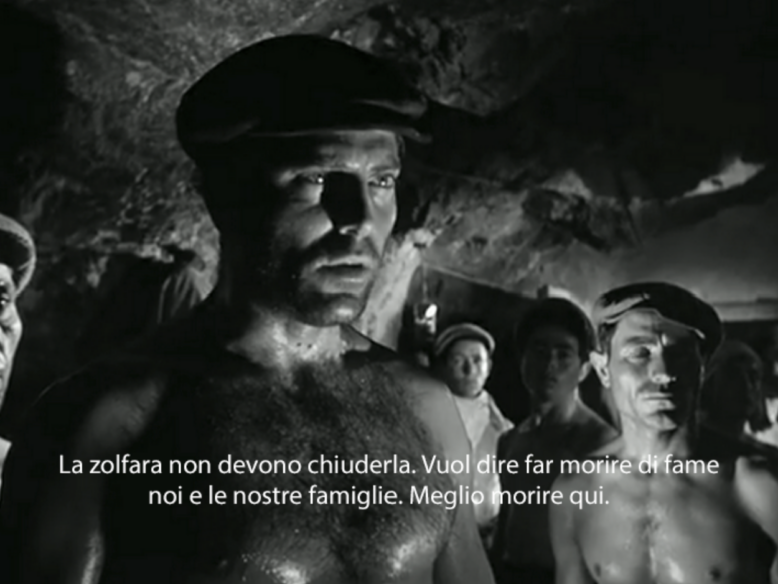

Informed that the mine is going to close, Saro, the leader of the sulfur miners, believes that they should go on strike and refuse to return to the surface. This close-up gives us visual information: it reveals not only his determination but also the heat endured by the workers in the mine. He says, “They must not close down the mine. It means making us and our families die of hunger. Better to die here.”

*Primo piano also means “foreground.”

Un sottotitolo – a subtitle

Text along the bottom of the screen that translates the spoken dialogue into the intended viewers’ language. Note: the crafting of subtitles is complex, and complete lines of dialogue are not reproduced, as a rule. For more on this, see “Writing Subtitles: Tips for Non-Professionals.”

Un primissimo primo piano or primo piano estremo – an extreme close-up

The camera focuses very close to a subject – often a face – to reveal detail, emotion, or significance. The intent is to create an intense connection with the audience or to call attention to the selected subject.

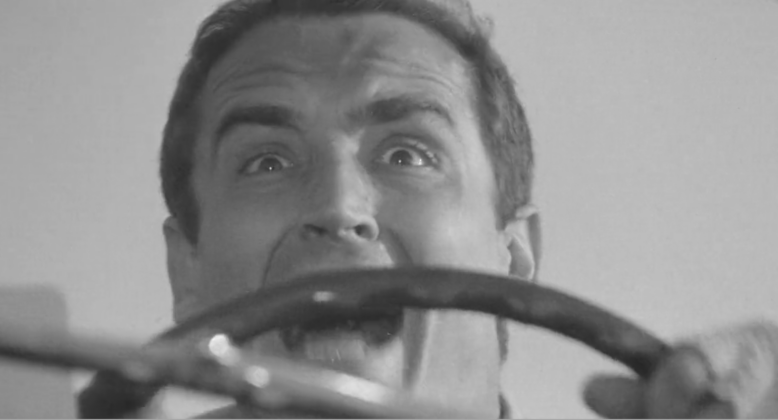

Bruno has been driving recklessly in his sports car, to show his young companion how thrilling life can be. At the story’s end, an extreme close-up reveals Bruno’s face as an oncoming truck bears down on them.

A close-up of Francesca’s face followed by an extreme close-up of the stolen necklace makes clear her distress at the sight.

Un campo lungo – a long shot

A shot from a distance that captures a wide area, establishing the setting. Often a character’s entire body is shown, to emphasize the smallness of an individual in a particular environment.

In a long shot within a factory, Nino’s white coat draws the viewer’s eye: a tiny figure moving between rows of towering machinery. This image of Nino as a tiny cog in the mechanism of the factory in Milan foreshadows his role in his hometown mafia in Sicily.

Un campo lunghissimo – an extreme long shot

A shot from a very long distance to capture a wide area, frequently as a panoramic view. Such a shot may simply establish the setting of the action. Alternatively, it may contrast the grandeur of the setting and the puny individual. By this device, the director is able to draw attention to a particular character’s isolation or insignificance.

Un campo medio – a medium shot

A shot from middle distance, including some of the surroundings. Normally, figures are shown from the waist up. This is a neutral shot and may be used for a variety of purposes.

After Mobbi, the industrialist, has his security guards set off smoke bombs to drive the residents out of the shantytown, Totò climbs a pole until he is above the cloud of smoke that covers the shantytown. Clinging to the pole, he gazes desperately into the distance.

Note: In Italian post-war films, extreme long shots are frequently used to depict new apartment buildings constructed during the so-called economic boom, which are contrasted with poor people in the foreground living in improvised housing – perhaps even in caves. For examples, see “Understand Italian Movies Better!” on the My Italian Circle blog.

Fuori campo – off-screen

An element of the action that is not visible on the screen – most often a line of dialogue.

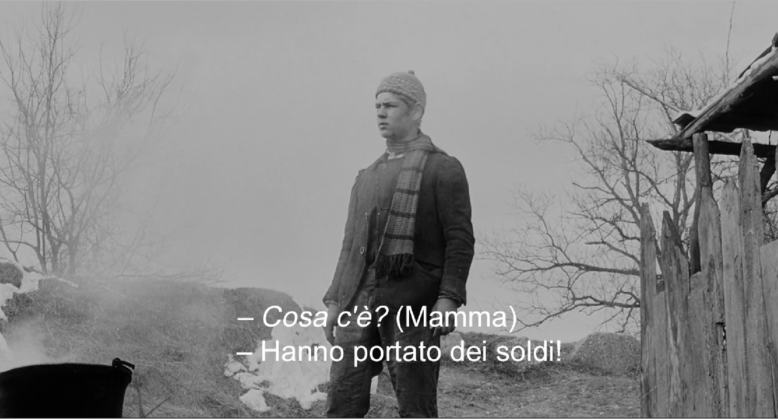

Omero brings money collected from the strikers to an impoverished Arab family. He gives it to the daughter, who is sitting outside. She grabs it and runs, calling to her mother. From inside the house – off-screen – her mother asks, “What is it?” and her daughter answers, “They brought money!”

Una panoramica – a pan

The camera makes a horizontal movement from a fixed spot to reveal new information, follow action, or establish the setting.

Francesca and Granata, thieves on the run, lean out of a train door. The camera pans along the car, showing a succession of quick scenes: a man lathering his face; a man who sniffs a flower until his companion slaps his hand; a man in an undershirt brushing his teeth; a woman combing her hair with a disdainful expression. Everyone is leaning out of the windows, looking at something. But what? At last, the pan answers the question.

Una carrellata – a tracking shot

The camera moves through a scene, following or running parallel to a subject. This places the viewer within the action, not merely observing it.

As he walks down an incline with four men in suits, Gino describes the accident: Signor Bragana was drunk and missed the curve. In this case, the tracking shot of Gino and the group is followed by a pan with (once more) a surprise ending: the ruined truck at the river’s edge and a policeman who stands by Bragana’s body.

In another tracking shot from the same film, Gino struggles through the crowd at a fair to reconnect with Giovanna and her husband Bragana. Scenes in which Italians of all kinds are crowded together – whether in a train station, at the beach, or in a town square – are a staple of later neorealist films.

Uno zoom – a zoom

The camera closes in on a subject – normally a person – for dramatic effect or to create a sense of intimacy. The zoom may be fast or slow. In this case, Italian adopts the English term.

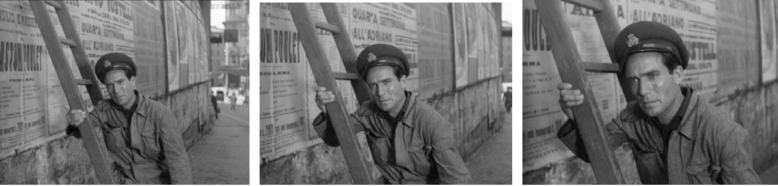

After chasing the thief who has taken his bicycle, Gino gives up and leans on his work ladder. The zoom shows us the utter despair on his face.

Una ripresa/inquadratura con gru – a crane shot

A shot from high up on a crane, which often includes panning across a broad landscape.

In this crane shot, women rice workers with linked hands look like paper dolls in the water; others walk single file along the narrow causeway dividing the pools. A line of trees runs across the rear.

Un taglio – A cut

The cut is fundamental to editing: an instantaneous transition from one shot or scene to another. Typically, cuts in post-war Italian films are seamless: in other words, they are unnoticed by the viewer. Cuts may simply move the story to the next scene, but they may also dramatize a transition.

In quick succession, a close-up of the lighthouse keeper shows that he’s ill; a cut to a shot over Karin’s shoulder shows the positions of the two characters; and a cut to a close-up of Karin’s face draws the spectator into the conversation. A final cut to show the concerned expression of the seamstress in the next room sets the scene in a larger context, spatially and emotionally.

Watching the film, no one would even notice these seamless cuts; they’re a familiar and fundamental part of cinematic storytelling.

Una dissolvensa – a dissolve

One shot fades out as the next shot fades in. This gradual transition is used to signify the passage of time, a change of location, or a thematic connection.

After Cabiria has walked all night with the good Samaritan, distributing food to those who live in caves, a dissolve indicates a lapse of time: afterwards, the dawn light shows us Rome far off in the distance, a reminder of how the more fortunate live.

Un taglio di corrispondenza – a match cut

A scene is cut so that the final sound or image matches the opening sound or image in the next scene.

After arriving in the workers’ dormitory, the accordionist plays a waltz and Mommino joins in on his guitar. In a match cut, the song continues without missing a beat into the next scene: Mommino and the accordionist play together while couples dance under the stars.

Un presagio – foreshadowing

Visual or auditory clues – dialogue, an object, action in a scene, etc. – that hint at later developments.

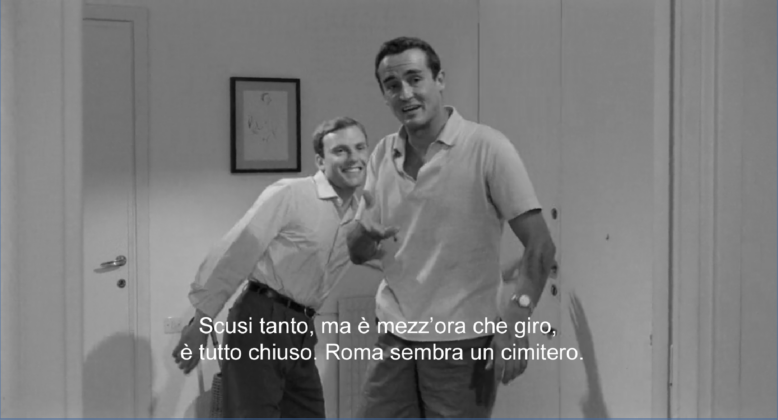

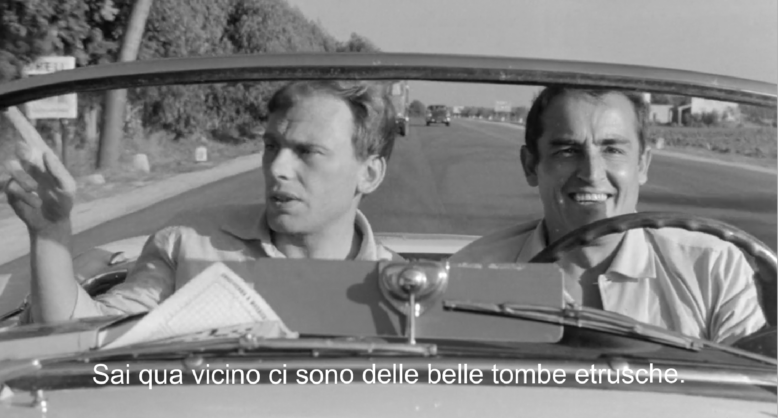

ll sorpasso contains several subtle foreshadowings of the death that ends the film. The viewer will not be aware of them until the last moments or even upon a second viewing. On first meeting Roberto, Bruno says, “I’m so sorry, but I’ve been driving around for half an hour and everything is closed. Rome seems like a graveyard.” It’s Ferragosto, when Italians typically leave town. Later, on their road trip, Roberto comments, “You know, nearby there are some beautiful Etruscan tombs.” Deciding idly to follow two German women who they see on the road, they end up at a cemetery. Later still, they pass a wrecked car and a body under a blanket.

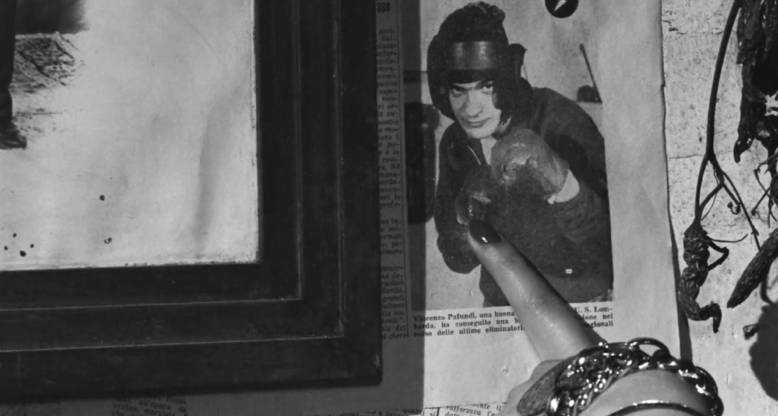

Un oggetto di scena – a prop

An item used in setting the scene. It may also hold specific meaning, often symbolic, especially when actors focus their attention on it.

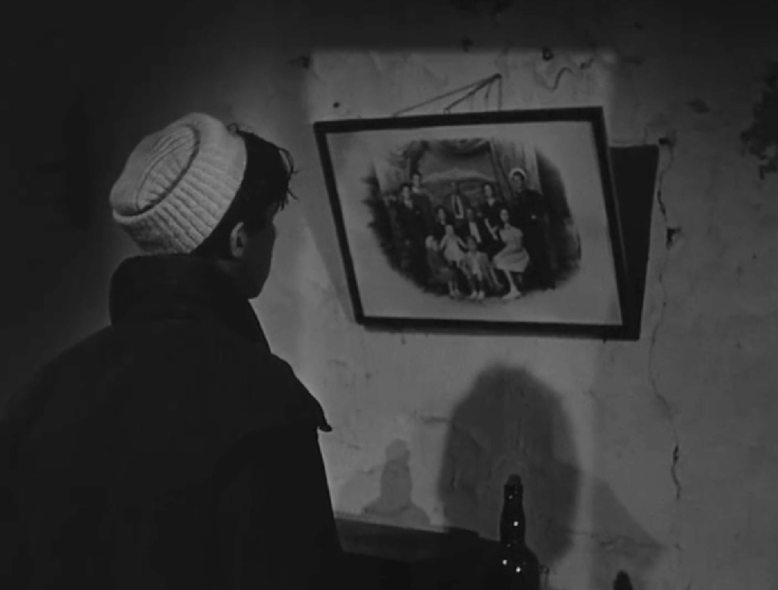

In La terra trema, a family portrait serves as a motif to show the feelings of Italians for their loved ones. Mara and Lucia, the daughters, gaze at it and talk about how much they miss the fishermen in their family – their grandfather, their brothers, and their father, all lost at sea. Later, Cola, one of the sons, apologizes to the men in the portrait because he is leaving the island to search for a better life. Finally, the camera draws attention to the portrait when the family is forced to move. Visconti used the same motif in Ossessione and in Rocco e i suoi fratelli.

2. The Creative Team and Their Work

Roma città aperta / Rome, Open City

Ladri di biciclette / Bicycle Thieves

Rocco e i suoi fratelli / Rocco and his Brothers

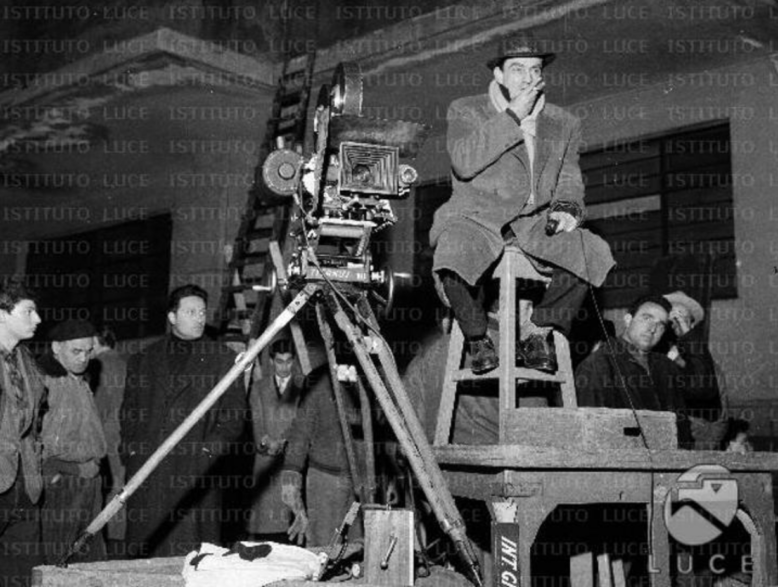

Il regista – the director

Directors guide the actors, crew, and heads of departments (such as cinematography, editing, production design, and costume) in bringing their vision of the film to life.

Above, some of the great directors of Italian post-war cinema (and of neorealism) Roberto Rossellini, Vittorio de Sica, and Luchino Visconti are shown sul set. (In all cases, unfortunately, the photographer is unknown.)

L’attore/l’attrice – the actor/actress

La comparsa – the extra

An actor with a (generally) nonspeaking part, who fills out crowd scenes and adds realistic context.

In Risate di Gioia, set in the Italian film industry, we see the protagonist, a third-rate actress, as an extra in a scene being shot for a sword and sandal movie. She’s played by the great Anna Magnani, who stars in the film with Totò and Ben Gazzara.

Il doppiatore / la doppiatrice – the dubber / voice actor

In post-production, the dubber reads the actor’s lines in the language of the intended audience. Until the 1970s, most Italian films were also dubbed in Italian, by voice actors other than those appearing on the screen. So, many of the actors’ voices that we know and love from Italian post-war films are not actually their own!

In the role of Nadia, a tragically mistreated prostitute, French actress Annie Girardot was dubbed by Italian actress Valentina Fortunato.

In Ossessione, the voice of lead actor Massimo Girotti was dubbed by Italian voice actor Gualtiero De Angelis (best known for dubbing the voice of Jimmy Stewart in Italian releases of his films).

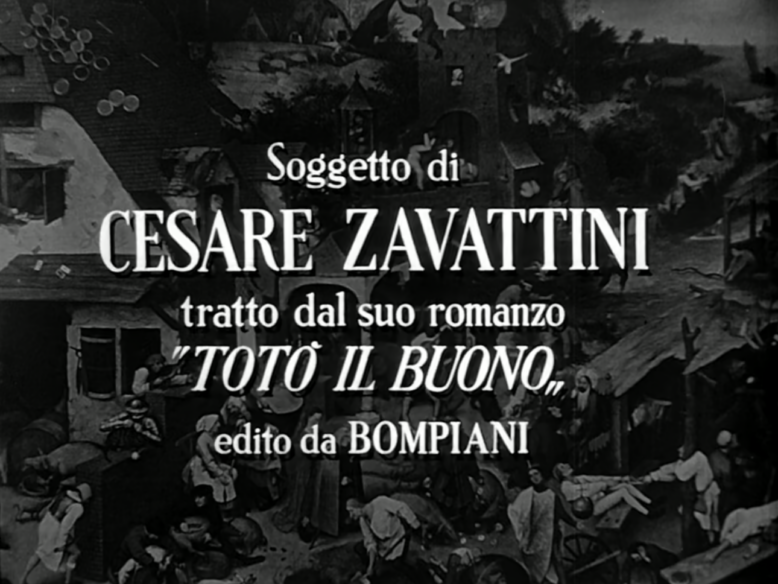

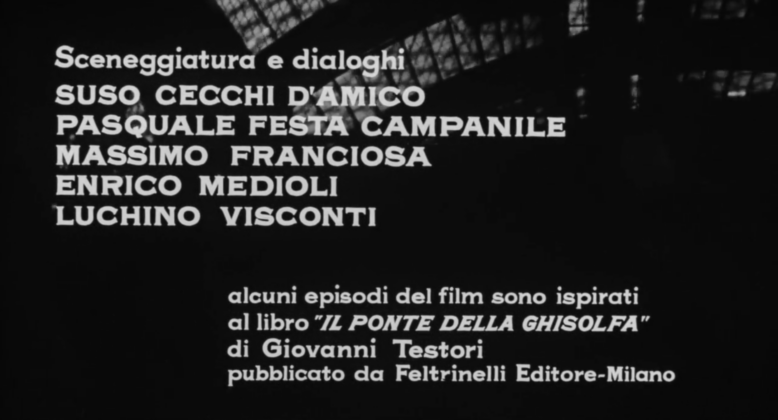

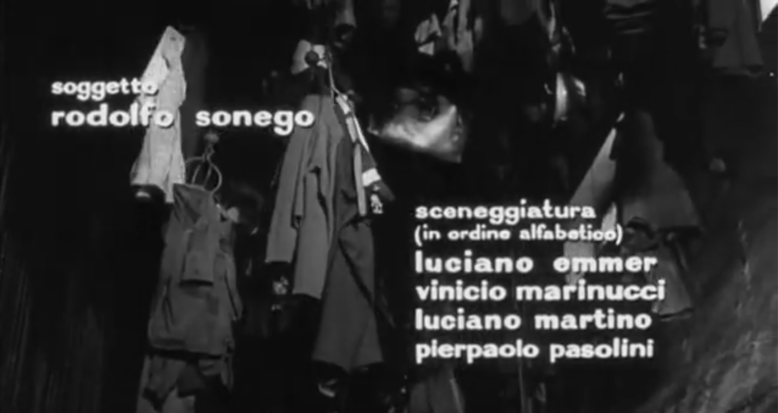

I titoli di apertura – the opening titles

The opening titles list the most important members of the film’s cast and crew.

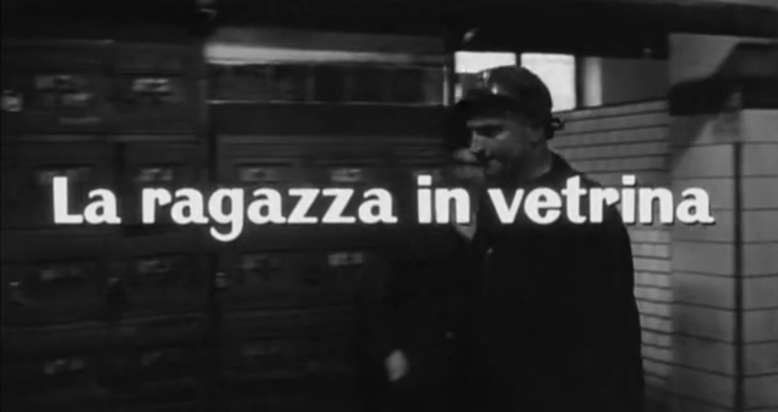

La sequenza dei titoli di testa – the opening title sequence

An opening title sequence displays the credits in a way that also introduces the subject or themes of the film. For example, they may be superimposed over the film’s opening action.

Il soggetto – story credit

The credit for the author of the source material, perhaps a novel or short story, or else a scenario written expressly for the film, as in the case of Roma città aperta (story by Sergio Amidei). Famously, Luchino Visconti did not credit James M. Cain for the story of Ossessione, which was clearly based upon Cain’s book The Postman Always Rings Twice.

La sceneggiatura – the screenplay

The screenplay contains all of the written instructions for cast and crew: dialogue, movement, and detailed notes regarding mood, expression, lighting, set decoration, and so on. Italian post-war films were often written by a team. Some of the most famous screenwriters of the post-war era are Cesare Zavattini, Suso Cecchi D’Amico, and Sergio Amidei. If you see their names, you’ll know it’s a film to watch!

Direttore della fotografia / Cinematographer: Lamberto Caimi

La fotografia – the cinematography

The Director of Photography collaborates with the director to create a look that matches the director’s vision. To that end, the DOP selects the lighting, the composition of shots, and the appropriate cameras and lenses and manages the camera operators.

In I fidanzati, the shots are sheer poetry: cinematographer Lamberto Caimi is equally adept at shaping industrial scenes in the north and graceful southern landscapes, conjuring a kind of peaceful solitude from a walk beside salt pans. In both cases, he finds the exquisite beauty in ordinary life.

Direttore della fotografia / Cinematographer: Ubaldo Arata

In Roma città aperta, which chronicles the struggles of Rome’s citizens during the German occupation, this final scene orchestrates location, actors, and framing to embody the director’s message: the boys who have been resisting the German military walk past a panorama of the city, mirroring the view that opened the film, with the dome of Saint Peter’s Basilica in the background. These weary, but indomitable boys are the future of Rome.

Direttori della fotografia / Cinematographers: Aldo Tonti and Domenico Scala

These shots in Ossessione convey a specific mood. In the morning light, Gino walks towards the camera, a halo of light around his head. The clouded sky fills more than half the frame; the beach fills the remainder. We hear a voice call his name, and his lover, Giovanna, emerges from the landscape to reconcile with him.

Montaggio – editing

After the film has been shot, the editor assembles the raw footage so as to tell the story and to reflect the director’s vision.

In the scene above, Nadia examines a family photo on the wall so as to identify the people in the room; she’s just introduced herself to the Parondi family as a neighbor. A seamless cut from a medium shot to a close-up highlighting Nadia’s painted fingernails and jewelry is followed by a cut to the next room, where Rosaria, the matriarch, is sorting through coats to find one for Nadia. This cut points up the contrast between the two women: Nadia, a prostitute who brags about the rich boxer she knows and his fancy car; and Rosaria, whose boys will find work in Milan shoveling snow.

La colonna sonora – the musical soundtrack

The music employed in a film. It may be specially composed or drawn from preexisting sources.

The most famous composer of Italian film scores is Ennio Morricone. However, others made valuable contributions. During the filming of Il cammino della speranza, the director (Pietro Germi) heard Giuseppe Cibardo Bisaccia, one of the sulfur miners, recite a poem in Sicilian about the hardships of their lives. He asked Franco Li Causi to set the poem to music, and the miners sing the song Vitti na’ Crozza several times in the film. It became quite popular in Italy.

I hope that you’ve enjoyed this survey of Italian film terms. For me, understanding these nuts and bolts, and the skill with which they are integrated and assembled, brings greater appreciation each time I watch these beloved films. I hope that is your experience, too.

For more coverage of classic Italian films, come visit www.liconoscevobene.net!

© 2026 Judy Cohen

Judy Cohen is the author of the blog www.liconoscevobene.net for Italian language students who love movies. Judy has a Master’s degree in Teaching English as a Second Language with 40 years’ experience, and a long time love of cinema, especially post-war Italian cinema. She’s also an Italian language student! Using her language teaching and learning skills, and working with her fantastic production team – Alberto Maio, Editor; Michela Badii, teacher; and Lucrezia Grussani, proofreader – she produces cineracconti (photo-stories) on her blog about classic Italian movies, including dialogue, scene descriptions, and cultural notes.