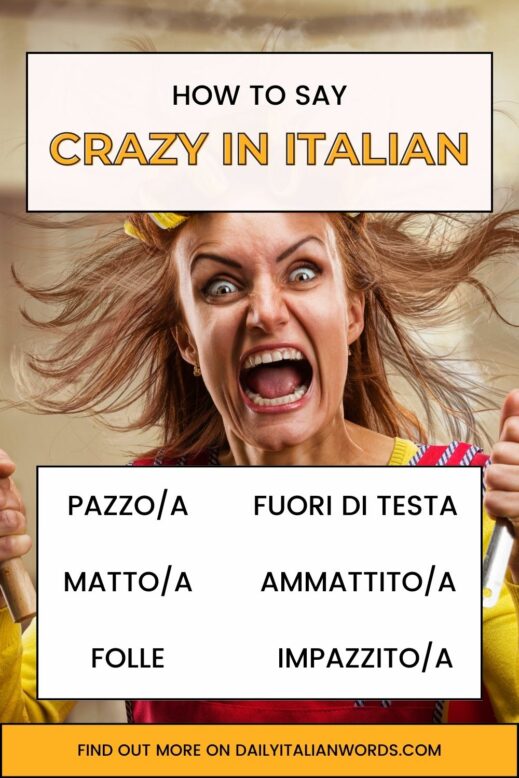

Do you think knowing how to say “crazy” in Italian might be useful to you as you’re learning the language of love? Some might think not, as it isn’t the most polite way to refer to a person, no matter how well you know them! However, learning this term also has its advantages.

By learning how to say “crazy” in Italian, you will soon notice just how many times this word is used in Italian pop songs, films and television shows. Plus, you will be able to recognise when someone dares to call you crazy in the head!

1. Pazzo / Pazza

The default term for “crazy” in Italian, which nearly all learners pick up within months of moving to Italy, is pazzo. The feminine equivalent is pazza and their respective plurals are pazzi and pazze.

Tu sei pazzo!

You’re crazy!

Pazzo is thought to derive from the Greek “πάθος” (pàthos), meaning “suffering” or “experience”. It can be used to describe someone with a mental illness but is also used in a hyperbolic sense to indicate someone who behaves bizarrely, or demonstrates wild and aggressive behaviour.

Mario è proprio pazzo. Va in giro con i pantaloni corti anche quando fa freddo.

Mario really is crazy. He goes out in shorts even when it’s cold.

It can be both an adjective (e.g. una persona pazza = a crazy person) or a noun (e.g. un pazzo = a crazy person / lunatic).

2. Matto / Matta

Whereas pazzo can describe someone with an ongoing mental illness, matto is usually associated with pure stupidity, foolishness or a temporary loss in rationality. For this reason, you cannot use matto to describe a cunning serial killer, but you could certainly use pazzo.

The feminine equivalent is matta while their respective plurals are matti and matte.

Non ti piace Clint Eastwood? Ma sei matto?

You don’t like Clint Eastwood? Are you crazy?

Matto most likely comes from the Late Latin “mattum”, which can ultimately be traced back to Maccus, a character in the Atellan Farce who is greedy, stupid, and constantly teased.

It appears in the expressions dare fuori di matto (to go crazy) and essere (un) matto da legare (to be a crazy person).

Matto can be both an adjective (e.g. una persona matta = a crazy person) or a noun (e.g. un matto = a crazy person / a fool).

3. Folle

Folle is yet another word that means “crazy” in Italian. Like pazzo, it is commonly used to indicate a generic mental disorder or mental illness but can also refer more generically to silly or wild people / things. Folle is both masculine and feminine, and the plural form is folli.

Spero che la tua idea folle non mi faccia perdere il lavoro!

I hope your crazy idea doesn’t cost me my job!

It can be both an adjective (e.g. una persona folle = a crazy person) or a noun (e.g. un folle = a crazy person/lunatic).

4. Impazzito / Impazzita

Impazzito and its feminine equivalent impazzita are the past participle of the verb impazzire, meaning “to go crazy”. For this reason, it can be translated as either “crazy” or “gone crazy/mad/nuts”.

Impazzire is a direct derivative of pazzo, so as you can imagine, the meaning of pazzo and impazzito is very similar.

Ma sei impazzito? Vergognati!

Have you gone nuts? You should be ashamed of yourself!

You can use this adjective to describe not only a state of madness, but also overwhelming passion, anger or frustration, as well as mechanical objects that cease to function properly. For example:

- È impazzito d’amore. = He is madly in love (lit. He’s gone mad with love)

- La bussola è impazzita. = The compass has gone haywire.

5. Ammattito / Ammattita

Considering that the verb impazzire was born from pazzo, it should come as no surprise that the same process took place with matto. Ammattito and the feminine ammattita both derive from the verb ammattire (to go crazy).

Although the literal definition of “becoming crazy” exists, the word is mostly used in a figurative way to describe overwhelming passion, anger or frustration. It is also used in the reflexive form ammattirsi.

Mi sono ammattito nel cercare di risolvere questo problema.

I went nuts trying to solve this problem.

6. Fuori di testa

Fuori di testa is the equivalent of the English expression “out of one’s mind”, although the literal translation is closer to “outside one’s head”.

Ma sei fuori di testa? Non puoi entrare senza permesso!

Are you out of your mind? You can’t go in without permission!

It appears in the following expressions:

- andare fuori di testa = to go crazy

- mandare (qualcuno) fuori di testa = to drive (someone) crazy

Quite often, fuori di testa is abbreviated to just fuori (e.g. Ma sei fuori? = Are you crazy?). You may also hear people say fuori come un melone (lit. outside like a melon).

Fuori di testa can also be a noun meaning “crazy person”.

7. Pazzesco

Pazzesco, despite deriving from pazzo, has a slightly different nuance. It is mostly used to refer to things that are senseless or unbelievable such as:

- una storia pazzesca = a crazy story (as in an unbelievable, wild story)

- un’idea pazzesca = a crazy idea (as in an idea that is wildly absurd)

Quello che mi dici è pazzesco. Faccio fatica a crederci.

What you’re telling me is crazy. I find it hard to believe.

The word has also gained the positive meaning of “exceedingly great” as in una fame pazzesca (a crazy hunger) or una voglia pazzesca (an insane desire).

8. Squilibrato / Squilibrata

Squilibrato and its feminine equivalent squilibrata are used somewhat less than the other terms we’ve seen so far, but that doesn’t mean they aren’t worth adding to your lexicon!

The literal meaning of these words is “unbalanced”, as they come from the verb squilibrare (to unbalance), but figuratively they also mean “crazy” in reference to a person’s unbalanced mental state.

Un tipo squilibrato mi ha insultato per strada.

A crazy guy insulted me on the street.

9. Avere qualche rotella fuori posto

Avere qualche rotella fuori posto is one of many idiomatic expressions you can use to describe someone who has an element of craziness about them. It literally means “to have a wheel out of place” but equates to the English expression “to have a screw loose”.

You may also hear the variants non avere tutte le rotelle a posto (lit. to not have all one’s wheels in place) and gli / le manca qualche rotella (lit. he’s / she’s missing some wheels).

Da come si comporta, direi che Marco ha qualche rotella fuori posto.

From how he behaves, I’d say Marco has a few screws loose.

10. Gli manca qualche venerdì

Let’s end off with this old-fashioned yet rather funny expression which literally means “He’s missing some Fridays”. According to il Corriere della Sera:

Il modo di dire allude, con molta probabilità, alla presunta stravaganza di chi nasce prematuramente. Costoro sono ritenuti “incompleti” e mancanti di qualche venerdì. E perché proprio venerdì? Perché al venerdì sono collegati tradizionalmente manovre scaramantiche, riti magici e pratiche occulte.

Translation: The saying probably alludes to the presumed strangeness of those born prematurely. They are considered “incomplete” and missing a few Fridays. And why Friday? Because Fridays are traditionally associated with superstitious schemes, magical rites and occult practices.

A quello sicuramente manca qualche venerdì. Guarda come cammina.

That guy is definitely missing a few screws. Look at how he walks.

You can also say Non ha tutti i venerdì (He doesn’t have all his Fridays).

Other “Crazy” Expressions in Italian

Here are a few key expressions with which you can enhance your Italian vocabulary.

“You are crazy” in Italian

- Tu sei pazzo / pazza.

- Tu sei matto / matta.

- Sei impazzito / impazzita.

“You drive me crazy” in Italian

- Mi fai impazzire. – Can be used to state that you really like someone, or that they annoy you.

- Mi fai perdere la testa. – Can only be used in a romantic sense.

- Mi fai uscire di testa.

“Are you crazy?” in Italian

- (Ma) sei pazzo / pazza?

- (Ma) sei matto / matta?

- (Ma) sei impazzito / impazzita?

“To go crazy” in Italian

- Impazzire = to go crazy

- Andare fuori di testa (lit. to go out of one’s head)

- Diventare pazzo / matto = (lit. to become crazy)

- Andare pazzo / matto per (qualcuno/qualcosa) = to go crazy for (someone/something)

- Ammattire = to go crazy

- Perdere la testa (lit. to lose one’s head)

Heather Broster is a graduate with honours in linguistics from the University of Western Ontario. She is an aspiring polyglot, proficient in English and Italian, as well as Japanese, Welsh, and French to varying degrees of fluency. Originally from Toronto, Heather has resided in various countries, notably Italy for a period of six years. Her primary focus lies in the fields of language acquisition, education, and bilingual instruction.