Ever since I was a young girl, I remember being fascinated by those in my class who were able to speak more than one language. It seemed to me like a mystical power to which only a select few had access.

My intense interest in languages didn’t end in primary school. Once in high school, I enrolled on a Japanese course, and later went on to study in Japan for two years as an exchange student where I became quite fluent.

Fast forward to 2008, the year I spontaneously decided to become an au pair in Torino, met my future husband, and discovered my true passion: Italian.

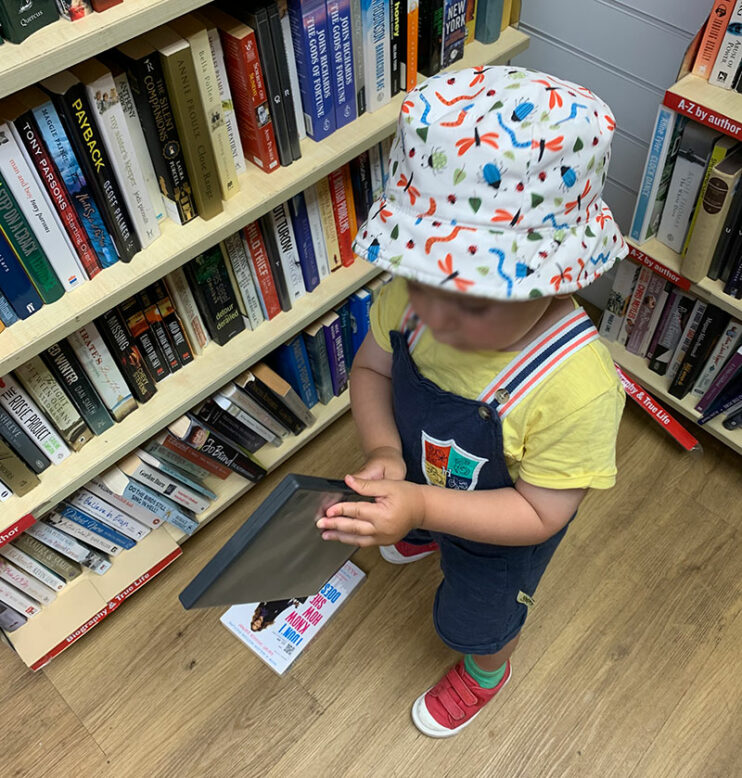

The language captured my imagination like no other, with its trilled Rs, round vowels and enchanting musicality. Although I now live in Wales, my love for Italian hasn’t diminished – in fact, it is stronger now than ever before because I have a young son whom I am raising in Italian!

Deciding to raise my son in Italian

My decision to raise my son E in more than one language took form long before I discovered I was pregnant. I had spent many years in Italy teaching other people’s children English, and I knew that I wanted the same kind of multilingual future for my children, if and when I had them.

Had we stayed in Italy, I would have certainly raised E in my native tongue, but when circumstances brought us to Wales, far from everything Italian, I knew we needed a change of plan.

One option was for my husband to speak to E in Italian, but because my husband is a bilingual French-Italian speaker, we decided it was best for him to focus on French. What’s more, he doesn’t spend nearly as much time as I do with E. In my mind, there was no other viable option – I had to be the one to pass on the language.

Three and a half years on and I can proudly say that I can count the number of times I’ve addressed E in English on one hand. Has it been tough at times? Yes. Do I have any regrets about my decision? Absolutely not.

But why are you doing this?

Good question! Ask a parent why they are raising their child in their non-native language, and you can expect a wide range of answers, from the extremely pragmatic to the emotional.

Some do it so that their children will have more opportunities in the future. Others might be inspired by the cognitive benefits learning a new language can bring.

In our case, we want E to be able to have an authentic relationship with his relatives in Italy, most of whom do not speak much English. We want him to be able to participate in our conversations without feeling lost or out of place. We also want him to feel connected to his origins, and there is no better way of achieving this than gifting him the language of his forebears.

Somewhat selfishly, I also want him to have the opportunity I always longed for – to grow up in a multilingual environment. You could say I’m living vicariously through him!

The challenges of raising a child in your non-native language

As a former English teacher at an Italian nursery school and au pair, I know all too well the challenges of teaching a child another language, be it your mother tongue or another language entirely. Here are a few I’ve encountered our my journey so far.

The “sponge” myth, exposure and need

The first challenge is the pervasive idea that “children are sponges”, or in other words, the myth that children simply absorb languages as if by magic. In truth, this so-called magic will occur only if two essential conditions are met: a) they receive sufficient exposure and b) feel a real need to use the language in their day-to-day life.

By sufficient exposure, I mean roughly one-third of a child’s waking hours actively using and hearing the target language. When you consider that most children attend daycare or school in the majority language, that doesn’t leave a lot of time for language learning!

As for need, if a child doesn’t feel compelled to use the language for whatever reason, be it lack of interest or the knowledge that their parents understand the majority language, they will mostly likely stop using it, even if the exposure condition is met.

So it falls on us, the parents, to make the most of the time we spend with our kids to pass on the target language.

This means we have to work harder than most parents. We have to talk more, describe things and situations in minute detail, engage in play and make believe games even when we’re tired or bored, and constantly look up words and expressions we don’t know. Every minute of every day is a potential “bilingual moment” and, as our children’s only source of constant input, the more we make good use of these moments, the more capable they will become in the target language.

I personally find the pressure to teach E Italian intellectually stimulating, as I’m always trying to come up with new things to say, using the correct grammar and terminology. And if I don’t know how to say something, I’ll look it up on the spot, or message an Italian friend for advice.

For example, E has recently become extremely passionate about vehicles. To keep up with his budding interest, I’ve had to learn all the names of the various means of transport in existence. In fact, I would bet that I know more truck names in Italian than I do in English!

In many ways, I am more proactive about studying Italian now than I ever was when I lived in Italy. If English were our main language of communication, I somehow doubt I would make the same effort.

Still, there are times when the pressure to perform can become overwhelming. You might feel guilty if you let an hour go by without speaking very much to your child, or if you allow them to watch the TV instead of interacting with them one-on-one. It’s at times like this that we must remind ourselves that progress rather than perfection is what counts. We’re all going to slip up now and then, but it’s better to move on than dwell on the mistakes.

Quality input

The previous topic of exposure and need segues nicely into the topic of how the quality of child-directed speech can influence a child’s language development.

As non-native speakers, the input we provide our children will never be as rich as that of a native speaker – that’s a fact. Non-native speakers naturally use fewer words and less varied vocabulary than native speakers, and even at an advanced level, we may garble our grammar and pronunciation on occasion.

So, how can we, as non-native speakers, overcome this? The answer is to incorporate as much external native input into your routine as possible, from television shows and books to regular interactions with native speakers.

In our case, E is exposed to my husband who speaks to me in Italian when E is present. Additionally, we do our best to arrange regular video calls with family in Italy, and expose him exclusively to Italian (and French) media at home in the form of books, television and music. Whenever we watch TV, I sit beside him and comment on what is going on, using the correct language provided by the show as a springboard. This past spring, we spent two months in Italy and France, and we are currently hosting an Italian exchange student for a semester, which has given him a massive boost in his speaking and comprehension. We’ve also taken him to a couple of Italian half-term clubs where he spends the entire day with an Italian teacher and other children who speak Italian at home, just like him.

If you live near big city, you can also sign your child up to an Italian school, attend meet-ups for Italian families, and eat out at Italian restaurants to provide them with as much exposure as possible. (Unfortunately this isn’t something we can offer to E on a regular basis, as we live out in the boondocks!)

Outside criticism

When I first announced that I’d be speaking to E exclusively in Italian, I was met with mixed reactions – which to be honest, I completely expected. After all, bilingual and trilingual households are the exception around here, not the rule.

Some people praised my decision, whereas others were confused, even critical. How could you raise your child in a language that’s not your own? Won’t he get confused? How will his poor little brain handle three languages? What if he picks up your mistakes/accent? These are just a few of the questions I’ve had to field from friends, family members and nosy grandmothers at the park.

I view these criticisms as an everyday reminder that many people still have an outdated view of what it means to be bilingual or multilingual. It is still commonly believed that knowing an additional language can hinder one’s cognitive abilities, whereas in actual fact, being bilingual has shown to improve multitasking and focusing on important information in adults and children. There is even strong evidence that it delays the onset of dementia symptoms in patients by approximately 4–5 years.

As for the doubts surrounding non-native input, it is true that initially, he will pick up my accent and mistakes. However, as long as he has other kinds of native input, such as the kind mentioned above, he has every opportunity to improve on his language skills and fix these mistakes later on, the same way an adult language learner would. The difference is that he will have a massive head start.

Someone I know once compared teaching a language to cooking. Just as you don’t have to be a master chef in order to teach your children the basics of cooking, you don’t have to be a native speaker to teach your child a language. You are simply laying the foundations so that they don’t have to start from scratch, and there is nothing stopping them from refining those skills later on.

Self doubt

One of the biggest hurdles to teaching your child your non-native language isn’t so much what others think of you, but the monster that is self doubt. No matter how fluent you are, there will always be moments when you feel as if you are failing. Perhaps you’ve made the same grammatical mistake for the 100th time, or you mispronounce a word you know how to say. It happens, and it’s only human.

To give you a real-life example, whenever I play trains with E, I struggle to remember all the different Italian verbs to describe their movement – swerving, racing, tumbling, crashing, doing a 360 degree spin. They all come to me instantaneously in English, but in Italian, I need a few seconds to think about it. And by the time I’ve pieced together the right expression, the moment has usually passed.

Whenever I’m faced with self doubt, I like to remind myself of the following quote attributed to Kató Lomb, a Hungarian interpreter and translator: We should learn languages because language is the only thing worth knowing even poorly.

“Even poorly” – that’s the takeaway phrase. If, at the end of our journey, E speaks Italian at an intermediate level with my Canadian accent, it is miles better than him having no knowledge of Italian whatsoever.

Emotional connection

One concern I did have before E was born was whether or not I could establish an emotional connection with him through Italian. It’s for this reason that some parents decide to use their second language with their kids in all situations except the most intimate, such as when they say “I love you“ for example.

As it turns out, I was very comfortable from the get-go, probably because Italian is such a massive part of my life in the form of my husband, family, friends and previous life experiences. I also feel like it is easier to be affectionate in Italian than English thanks to the sheer number of terms of endearment – cute pet names like cucciolo (cub), tesoro (treasure) and of course, amore mio (my love).

Of course, if you have no emotional connection to your target language, you may find it difficult to use it all the time, and there’s no shame in this! I personally use Italian all the time, as I feel comfortable doing so and would find it confusing to switch back and forth, but that doesn’t mean you have to do the same. Some parents use the target language just a few days a week, or during specific routines or in certain places such as in the home. There is no right or wrong answer – you simply have to do what’s best for you and your family.

Update: A fascinating byproduct of consistently conversing with E in Italian is that my parents have developed a passive understanding of the language, even though they’ve never formally studied it!

Final thoughts

Raising one’s child in one’s non-native language certainly isn’t for everyone. It takes courage, determination, patience, and a thick skin in the face of criticism, negativity towards bilingualism, and personal self doubt. But most importantly, it requires an undying passion for the target language and an insatiable desire to pass it on.

Now that E is effortlessly juggling English, Italian and French (and soon Welsh once he enters the Welsh school system), I feel more encouraged than ever before to continue on our Italian journey, for however long it may last. Once he reaches school age and English becomes the dominant language in his life, the dynamic may change, but at least I’ll know that I’ve given him an amazing start.

If you are on the fence about using Italian, or another language, with your child, my advice would be to go for it. You absolutely have nothing to lose in trying. After all, a little bit of Italian is far better than no Italian at all.

Recommended creators who are raising their children in their non-native language:

Heather Broster is a graduate with honours in linguistics from the University of Western Ontario. She is an aspiring polyglot, proficient in English and Italian, as well as Japanese, Welsh, and French to varying degrees of fluency. Originally from Toronto, Heather has resided in various countries, notably Italy for a period of six years. Her primary focus lies in the fields of language acquisition, education, and bilingual instruction.